Considerations

What to test: Selecting the right benchmark

When choosing what to benchmark, consider your project’s context and goals:

Replicating existing work: If similar methods already exist, benchmark your tool against them to demonstrate improvements or different trade-offs (e.g., speed vs. accuracy).

Establishing a new baseline: If your method is novel, create a high-quality benchmark to define a reference point for future tools to compare against.

Head-to-head comparisons: If comparing multiple tools, use publicly available datasets and tools where possible to ensure transparency and reproducibility. The benchmark should reflect real-world use cases and rely on high-quality data.

Social Factors - Project management

How to Get Community Buy-in for commitment for benchmarking, best practices, metrics, reporting, and standardization

Projects: Projects need to have sufficient funding to allocate resources for this. This includes both human resources as well as computing resources as scientific benchmarks often require a lot of compute time

Directors: Once the project leadership has committed to the project, Directors should check on progress to drive the project forward and ensure that the project managers and implementers have the resources needed

Project managers: Project managers should identify a small project leadership team of 2-4 people to drive the project forward. This includes outlining the project, identifying milestones and sub-deliverables, estimating timeframes, setting up regular meetings to ensure things are moving forward, and interacting with the individuals who will implement the benchmarks. Note that the project managers are responsible for implementing the benchmarking framework, not the individual benchmarks themselves! Ideally, individuals who aren’t close to the team (developers) and haven’t been instructed by the team should implement specific benchmarks based on documentation alone that was created by the project management team.

Individuals: These are the developers implementing specific benchmarks (NOT the benchmarking framework).

Users

- Partners: If these are industry partners that are partly responsible for setting up the benchmark, then they will be part of the project management team. Partners will run the benchmark on their own private dataset and will share the results publicly, but without the private dataset.

- Other Academics In The Same Field: Will be able to see the results of the benchmark but not the private datasets, if applicable. In this case, the publication might not include the data itself but statistical averages of the dataset across various dimensions. Or the publication might include running the method on a public dataset

Who owns the benchmarks?

It is advisable to come to an agreement before the implementation of the benchmarks on who owns what, who is responsible for what, who can sign off on specific benchmarks, and who maintains them. For maintainers, keep in mind (1) the scientific expertise for maintaining the benchmark (which might require very specific scientific expertise), and (2) the technical expertise to maintain them either on the specific hardware or ideally, maintaining the whole framework that runs a set of benchmarks.

High Standards

Scientific benchmark sets and benchmarking tests should follow high standards, ideally the Standards and best practices described below.

Technical requirements

Language and software requirements: Think about the programming language (C++, Python, other) and software requirements (specific software tools, versions, environments) before implementing anything. Add these to the list of requirements and think about the simplest possible scenario / fewest requirements that you can get away with.

Continuous testing infrastructure requirements When set up well, scientific benchmarks can be run on a continuous basis. However, this requires software development work upfront to create a framework in which various tests can be run in an automated manner. An example of such a general framework is described in REF 7. Further details about the implementation can be found in the implementation section below.

Computing expense

Determining your needs:

- Scientific benchmarks often require substantial compute power to run

- For a single benchmark: you need to think about how much compute power (and hardware requirements) your benchmark requires and how often you want to run it

- For a benchmark suite: you need to think about how much compute power (and hardware requirements) each benchmark needs, how many benchmarks you have and how often you want to run each of them.

- Example: Rosetta runs their scientific benchmarks about once a week - this decision was made based on the available compute power and the compute requirements and runtimes for each benchmark

Stakeholder Buy - in:

- Stakeholder buy-in for computing expenses in scientific benchmarks involves securing approval and support from project leaders, funders, and collaborators by clearly communicating the value and necessity of the benchmarks. This includes demonstrating how benchmark results will inform critical decisions, improve system performance, and ensure long-term research sustainability. Providing transparent cost breakdowns, expected outcomes, and potential ROI helps align stakeholders’ goals with project needs, fostering trust and commitment.

Scientific requirements

Statistics for benchmark sets: benchmarks sets should be relevant, diverse, and standardized. All elements in the benchmark set should be processed in the same way.

Benchmark methods: benchmark methods should be high quality, meaning they should be relevant, scalable, robust and stable, and include diverse scenarios. The broader the method is, the higher its impact will be because more people will be able to use it.

Documentation: Documentation should include not only instructions for running benchmarks and interpreting results, but reference to publications that report results for comparison and explanation of the relevant methods

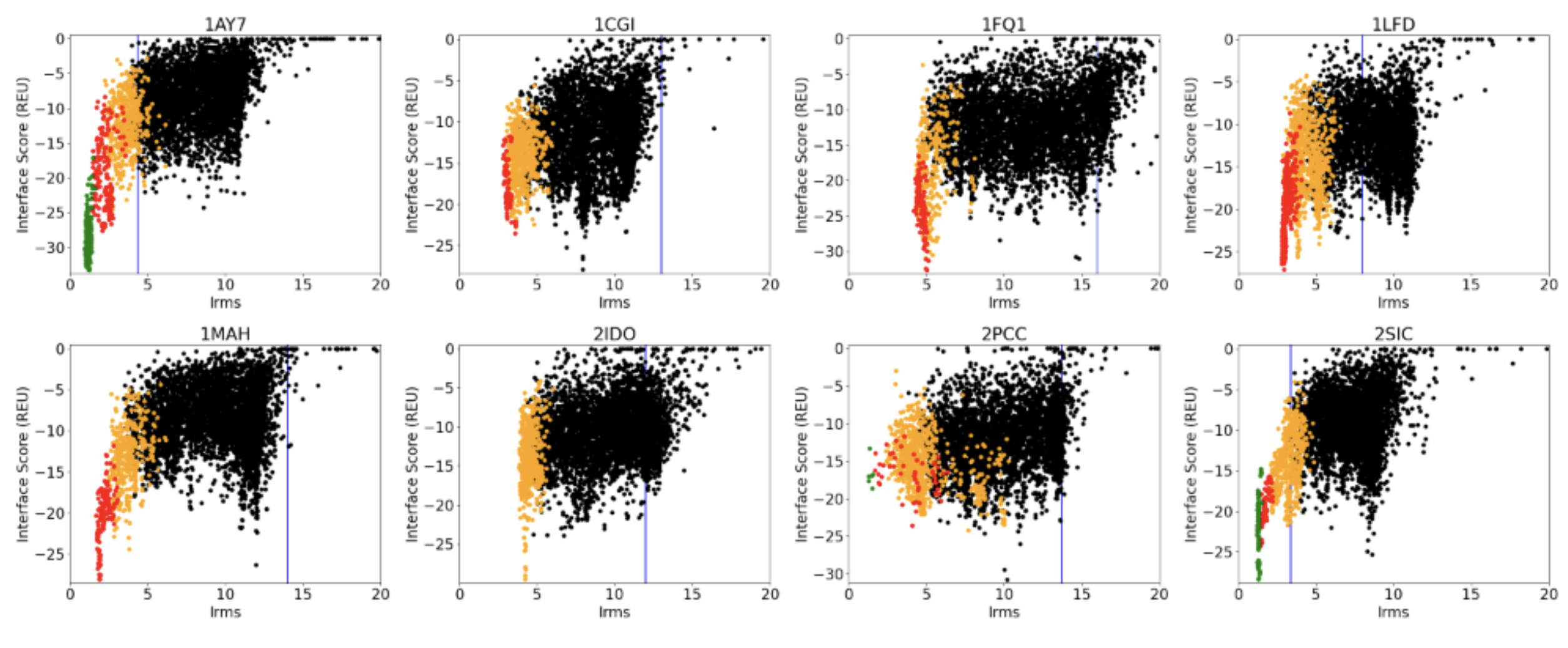

Cutoffs to define pass/fail criteria: cutoffs to define pass/fail criteria are important to allow automatic evaluation of the scientific benchmark. Say, if a benchmark is running automatically, one can encode a failure criteria that triggers a response, such as informing the maintainer that this particular test failed and needs to be looked into - at least to understand why the failure occurred. One possible way to define a failure criterion is to run the test three times, and add a percentage (like 10-20%) to the main metric that is being tracked for each benchmarking test case. F.ex. below is part of the protein-protein docking benchmark where each plot represents a different protein, the metrics are interface score vs. interface RMSD and each dot in the plots represents a model created. The blue vertical line below represents the cutoff for each protein.

Lowest barriers to contributions

The lower the requirements for contributions are, the easier it is for people to contribute and the larger the impact will be and the longer the benchmarks will persist